Addison Baena

When we talk about sound, what usually comes to mind are the vibrations that travel through the air, reaching our ears and allowing us to hear. So, decibels, the ‘dB’ you often see, in this case, measure the Sound Pressure Level (SPL). Other common types of decibels are dB(u), which measures sound as voltage in an analog system, or dB(FS) for sound as data in the digital world. But in the end, dB is just a way to condense perceived changes in loudness into a workable scale, and it comes with a few tricks for easy calculations.

You may heard these tricks before, but phrased in ways that contradict each other:

1#: Doubling the volume is a 3dB increase.

2#: Doubling the volume is a 6dB increase.

3#: Doubling the volume is a 10dB increase.

Misunderstandings happen when we are too vague with the term volume. Each of these tricks has specific conditions where it can be used. Let’s write these tricks again but be very specific about the conditions that would make the trick true.

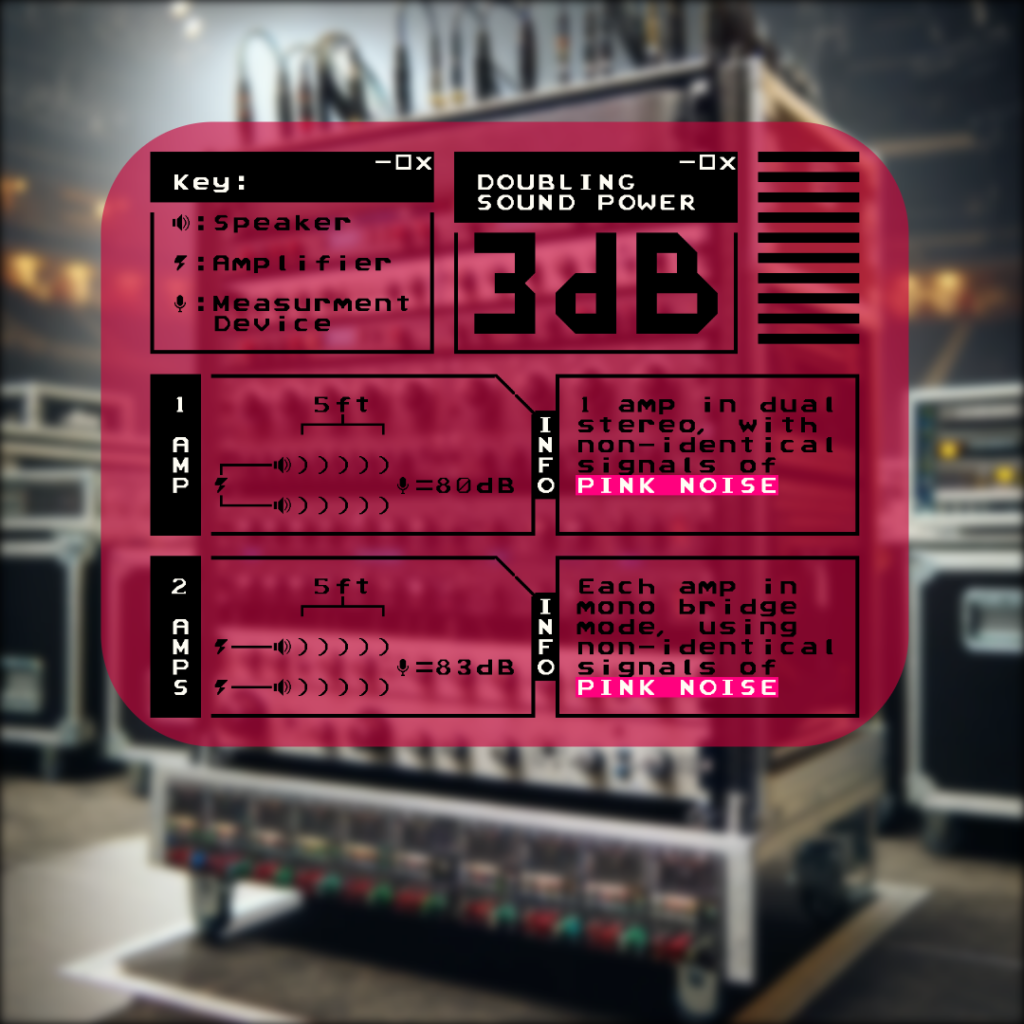

#1 Doubling the sound “power” is a 3dB increase.

Here are some situations where we would use trick one. We have two passive speakers running off one amplifier. Let’s say they measure at 80dB at 5 feet away when everything is turned all the way up. Now you add another amplifier so that each speaker gets its own. You’ve now doubled the power, and theoretically, there should be an increase of 3dB at the point you measured. Now the dB(SPL) meter is reading 83dB. Now what if the speakers are placed exactly next to each other, playing the exact same signal, and the measurement device is placed where the waves from both speakers are in phase and summing? The compression waves summing together in the air would actually be a doubling of amplitude situation, so you could expect 86dB in the area that’s perfectly in phase. Once you’re out of that alley, though, and in areas where signals may be interfering a little more, the dB increase will drop again, moving more towards 83dB depending on the phase.

Let’s change the situation again. At this point, we have 2 speakers running off 2 amplifiers. Let’s say they’re playing different channels of pink noise, so no in-phase waves are doubling amplitude in this situation. We’re still at 83 decibels. Now, let’s add 2 more speakers but keep the number of amps the same. With 4 speakers and 2 amplifiers, we will still only read 83dB. We’ve doubled the speakers, but since the total power is the same, our maximum volume won’t get any louder.

We can also apply trick #1 in situations that don’t deal with power in watts. By strumming an acoustic guitar, the mechanical energy producing the sound is the strings. Add a second guitar, and you’ve doubled the power, a 3dB increase. Sound power can be vibrating vocal cords, or a vibrating membrane on a drum, or vibrating air across a pipe like a flute. So doubling the number of any of these instruments is always using the rule of doubling sound power.

#2 Doubling the sound wave’s amplitude is a 6dB increase.

Now, let’s talk about trick #2. If you split an XLR signal with a Y cable, each split is going to be 6dB lower since the amplitude got halved. The opposite would be true in cases where two identical signals are summed using a Y cable. A 6dB increase. If the signals aren’t identical, it may be a bit less than 6dB, depending on how signals are interfering with each other. Here’s a situation where this may come up. You set your input gain on your board for a vocalist. A while later after you’ve got everyone’s monitor mix set, the vocalist puts a passive splitter on their mic (where did they even get that?) because they have a personal in-ear system they run their vocals to just to hear themselves. Not a problem; you would just bring their input gain up 6dB to compensate for the volume drop. This way, the vocalist isn’t suddenly 6dB quieter in everyone’s monitor mix.

#3 We will subjectively perceive something as twice as loud with a 10dB increase.

Trick number 3 might be used if you’re in a sound check and someone says something like, “Make me twice as loud in my monitor.” Now we’re dealing with subjective loudness, so we’ll bring the musician’s fader up 10dB. But “twice as loud” may sound different to everybody, so remember that 10dB isn’t so much a rule here, just a good place to start.

If you can figure out whether you’re dealing with the power to produce sound, or the amplitude wave doubling, or someone wanting a subjective doubling of sound, you’ll know which trick to use.

Addison is an Audio tech at Warner AV, with 10 years of Live events experience.